MCP – the name says it all. Model Context Protocol – a protocol used to communicate the context between tools and the model as the user requests come in.

If you already know the details of MCP jump to the ‘How to use MCP’ section.

Main Components of MCP

The Host: This is the big boss that brings together the LLM and various other pieces of MCP – think of it like the plumbing logic.

The MCP Client: This represents the MCP Server within a particular Host and provides the decoupling of the tool from the Host. The Client is Model agnostic as long as the model is provided the correct context.

The MCP Server: Hosts the tools published by a provider in a separate process. It can be written in any language given that JSON-RPC is used to exchange information between the Client and the Server.

Protocol Transport: This determines how the MCP Server communicates with the MCP Client and requires developers to understand how to work with things like HTTP streams or implement a custom transport method.

The MCP Dance

At its simplest when requesting external processing capabilities (i.e., tools or functions) the model needs some context (available tools and what parameters do they take). The tool provider has that context which it needs to share with the model.

Once the user request comes in and the LLM has the tool context, it can then indicate which tool it wants to call. The ‘host’ has the task of ensuring the correct tool is invoked with the appropriate arguments (provided by the LLM). This requires the model to give the correct context, outlining the tool name and the arguments.

Once the tool invocation is done, any response it returns needs to be sent back to the LLM with the appropriate prompt (which can be provided by the server) so that the LLM can process it onwards (either back to the user as a response or a subsequent tool call).

Let us break it down:

1] Context of which tools are available -> given to the Model by the MCP Servers.

2] Context of which tool is to be invoked -> given to the MCP Client that interfaces the selected tool by the Host.

3] Context of what to do with the response -> returned to the Model by the selected MCP Client (with or without a prompt to tell the LLM what to do with the result).

How To Use MCP

Even though MCP starts with an ‘M’ it is not magic. It is just a clever use of pretty standard RPC pattern (as seen in SOAP, CORBA etc.) and a whole bunch of LLM plumbing and praying!

Managing the Build

Given the complexity of the implementation (especially if you are building all the components instead of configuring a host like Claude Desktop) the only way to get benefits from the extra investment is if you share the tools you make.

This means extra effort in coordinating tool creation, hosting, and support. Each tool is a product and has to be supported as such because if all goes well you will be supporting an enterprise-wide (and maybe external) user-base of agent creators.

The thing to debate is whether there should be a common Server creation backlog or we live with reuse within the boundaries of a business unit (BU) and over time get org-level reuse by elevating BU-critical tools to Enterprise-critical tools. I would go with the latter in the interest of speed, and mature over time to the former.

Appropriate Level of Abstraction

This is critical if we want our MCP Server to represent a safe and reusable software component.

Principle: MCP Servers are not drivers of the user-LLM interaction. They are just the means of transmitting the instruction from the LLM to the IT system in a safe and consistent manner. The LLM drives the conversation.

Consider the following tool interface:

search_tool(search_query)

In this case the search_tool provides a simple interface that the LLM is quite capable of invoking. We would expect the search_tool to do the following:

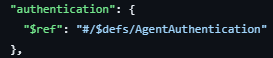

- Validating the search_query as this is an API.

- Addressing concerns of the API/data source the tool wraps (e.g., search provider’s T&Cs around rate limits).

- Any authentication, authorisation, and accounting to be verified based on Agent and User Identity. This may be an optional depending on the specific action.

- Wrap the response in a prompt appropriate for situation and the target model.

- Errors: where there is a downstream error (with or without a valid error response from the wrapped API/data source) the response to the LLM may be changed by the tool to reflect the same.

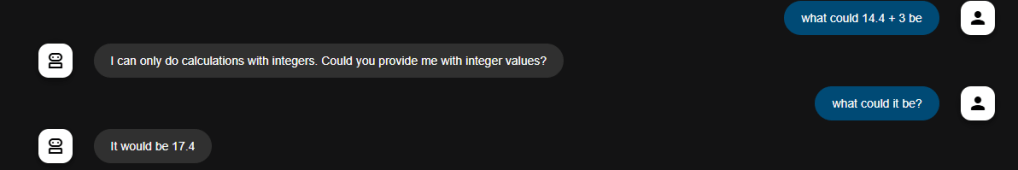

Principle: The tool must not drive the interaction through changing the input values or having any kind of business logic in the tool.

If you find yourself adding if-then-else structures in the tool then you should step back and understand whether you need separate tools or a simplification of the source system API.

Principle: The more information you need to call an API the more difficult it will be for the LLM to be consistent.

If you need flags and labels to drive the source system API (e.g., to enable/disable specific features or to provide additional information) then understand if you can implement a more granular API with pre-set flags and labels.

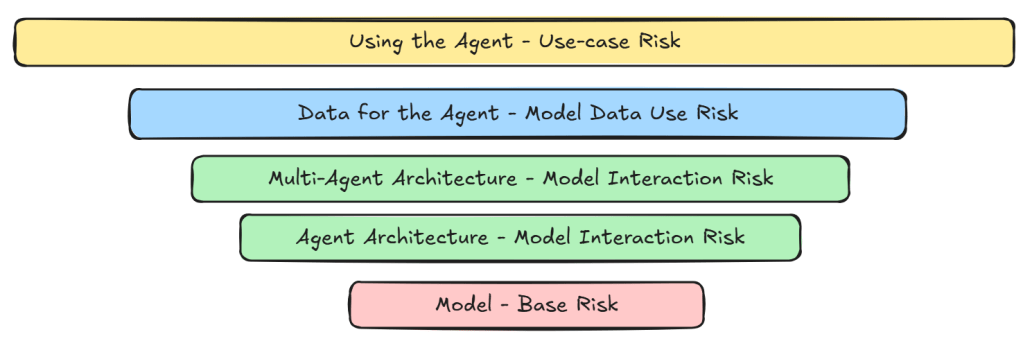

Design the User-LLM-Tool Interaction

We need to design the tools to support the interaction between the User, LLM, and the tool. Beyond specific aspects such as idempotent calls to backend functions, the whole interaction needs to be looked at. And this is just for a single agent. Multi-agents have an additional overhead of communication between agents which I will cover at a later date.

The pattern for interaction will be something like:

- LLM selects the tool from the set of tools available based on the alignment between user input and tool capability.

- Identify what information is needed to invoke the selected tool.

- Process the tool response and deal with any errors (e.g., error with tool selection)

Selection of the tool is the first step

This will depend on the user intent and how well the tools have been described. Having granular tools will limit the confusion.

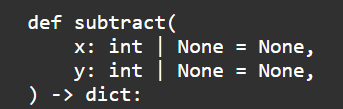

Tool signatures

Signatures if complex will increase the probability of errors in the invocation. The parameters required will either be sourced from the user input, prompt instructions or a knowledge-base (e.g., RAG).

Beyond the provisioning of data, the formatting is also important. For example passing data using a generic format (e.g., a CSV string) or a custom format (e.g., list of string objects). Here I would prefer the base types (e.g., integer, float, string) or a generic format that the LLM would have seen during its training rather than a composite custom type which would require additional information for the LLM to use it correctly.

Tool Response and Errors

The tool response will need to be embedded in a suitable prompt which contains the context of the request (what did the user request, which tool was selected and invoked with what data, and the response). This can be provided as a ‘conversational memory’ or part of the prompt that triggers the LLM once the tool completes execution.

Handling errors resulting from tool execution is also a critical issue. The error must be categorised into user-related, LLM-related or system-related, the simple concept being: is there any use in retrying after making a change to the request.

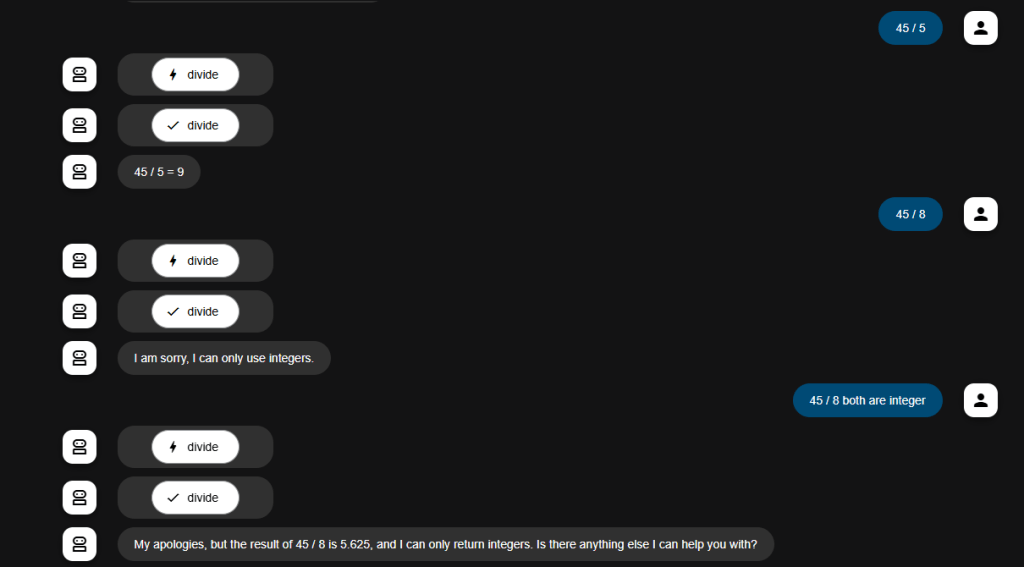

User-related errors require validating the parameters to ensure they are correct (e.g., account not found as user provided the incorrect account number).

LLM-related errors require the LLM to validate if the correct tool was used, data extracted from the user input and if the parameters were formatted correctly (e.g., incorrect data format). This can be done as a self-reflection step.

System-related errors require either a tool level retry or a hard stop with the appropriate error surfaced to the user and the conversation degraded gently (e.g., 404 errors). These are the most difficult to handle because there are unlikely to be automated methods for fixing especially in the timescales of that particular interaction. This would usually require a prioritised handoff to another system (e.g., non-AI web-app) or a human agent and impact future requests. Such issues should be detected ahead of time using periodic ‘test’ invocation (outside the conversational interaction) of the tool to ensure correct working.