The first part of this post (here) talks about how Generative AI models are nothing but functions that are not well behaved. Well-behaved means functions that are testable and therefore provide consistent outputs.

Functions misbehave when we introduce randomness and/or the function itself changes. The input and output types of the function is also important when it comes to understanding its behaviour and testing it for use in production.

In this post we take a deep dive into why we should treat Gen AI models as functions and the insight that approach provides.

Where Do Functions Come Into The Picture?

Let us look at a small example that uses the transformer library execute a LLM. In the snippet below we see why Gen AI models are nothing but functions. The pipe function wraps the LLM and the associated task (e.g., text generation) for ease of use.

output = pipe(messages, **configs)

The function pipe takes in two parameters: the input (messages) that describes the task and a set of configuration parameters (configs) that tune the behaviour of the LLM. The function then returns the generated output.

To simplify the function let us reformulate it as function called llm that takes in some instructions (containing user input, task information, data, examples etc.) and some variables that select the behaviour of the function. Ignore for the moment the complexity hiding inside the LLM call as that is an implementation detail and not relevant for the functional view.

llm(instructions, behaviour) -> outputLet us look at an example behaviour configuration. The ‘temperature’ and ‘do_sample’ settings tune the randomness in the llm function. With ‘do_sample’ set to ‘False’ we have tuned all randomness out of the llm function.

configs = {

"temperature": 0.0,

"do_sample": False,

}

The above config therefore makes the function deterministic and testable. Given a specific instruction and behaviour that removes any randomness – we will get the exact same output. You can try out the example here: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/Phi-3.5-mini-instruct. As long as you don’t change the input (which is a combination of the instruction and behaviour) you will not notice a change in the output.

The minute we change the behaviour config to introduce randomness (set ‘do_sample’ to ‘True’ and ‘temperature’ to a value greater than zero) we enter the territory of ‘bad behaviour’. Given the same instruction we get different outputs. The higher the temperature value more will be the variance in the output. To understand how this works please refer to this article. I next show this change in behaviour through a small experiment.

The Experiment

Remember input to the llm function is made up of an instruction and some behaviour config. Every time we change the ‘temperature’ value we treat that as a change in the input (as this is a change in the behaviour config).

The common instruction across all the experiments is ‘Hello, how are you?’, which provides an opening with multiple possible responses. The model used is Microsoft’s Phi-3.5-mini. We use ‘sentence_transformers’ library to evaluate the similarity of the output.

For each input we run the llm function 300 times and evaluate the similarity of the outputs produced. Then we change the input (by increasing the temperature value) and run it again 300 times. Rinse repeat till we reach the temperature of 2.0.

The Consistent LLM

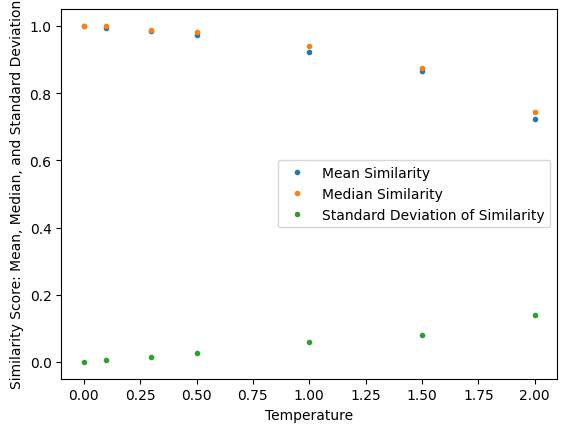

The first input uses behaviour setting of ‘do_sample’ = ‘False’ and ‘temperature’ = 0.0. We find no variance at all in the output when we trigger the llm function 300 times with this input. This can be seen in Figure 1 at Temperature = 0.00, where the similarity between all the outputs is 1 which indicates identical outputs (mean of 1 and std. dev of 0).

The llm function behaves in a consistent manner.

We can create tests by generating input-output pairs relevant to our use-case that will help us detect any changes in the llm function. This is an important first step because we do not control the model lifecycle for much of the Gen AI capability we consume.

But this doesn’t mean that we have completely tested the llm function. Remember from the previous post – if we have unstructured types then we are increasing the complexity of our. Let us understand the types involved by annotating the function signature:

llm(instructions :str, behaviour :dict) -> output :strGiven the unstructured types (string) for instructions and output, it will be impossible for us to exhaustively test for all possible instructions and validate output for correctness. Nor can we use mathematical tricks (like induction) to provide general proofs.

The Inconsistent LLM

Let us now look at how easily we can complicate the above situation. Let us change the input by only changing the behaviour config. We now set ‘do_sample’ = ‘True’ and ‘temperature’ = 0.1. This change has a big impact on the behaviour of our llm function. Immediately we start seeing the standard deviation of the similarity score for the 300 outputs start increasing. The mean similarity also starts to drop from ‘1’ (identical).

As we increase the temperature (the only change made to the input) and collect 300 more outputs we find the standard deviation keeps increasing and the mean similarity score continues to drop.

We start to see variety in the generated output even though the input is not changing.

The exact same input is giving us different outputs!

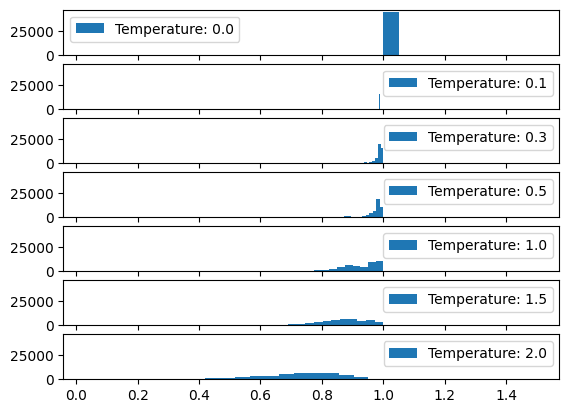

Let us see how the distribution of the output similarity score changes with temperature.

We can see in Figure 2 starting from a temperature of 0.0 we see all the outputs are identical (similarity score of 1). As we start increasing the temperature we find a wider variety of outputs being produced as the similarity score distribution broadens out.

At temperature of 1.0 we still find many of the outputs are still identical (grouping around the score of 1) but we see some outputs are not similar at all (the broadening towards the score of 0).

At temperature of 2.0 we find that there are no identical outputs (absence of score of 1), instead we find the similarity score spread between 0.9 and 0.4.

This makes it impossible to prepare test cases consisting of checking input-output value pairs. Temperature is also just one of many settings that we can use to influence behaviour.

We need to find new ways of testing mis-behaving functions based on semantic correctness and suitability rather than value checks.

Why do we get different Outputs for the same Input?

The function below starts to misbehave and provides different outputs for the same input as soon as we set the ‘temperature’ > 0.0.

llm(instructions :str, behaviour :dict) -> output :strWhen we are not changing anything in the input something still changes the output. Therefore, we are missing some hidden information that is being provided to the function without our knowledge. This hidden information is randomness. This was one of the sources of change we discussed in the previous post.

Conclusions

We have seen how we can make LLMs misbehave and make them impossible to test in standard software engineering fashion by changing the ‘temperature’ configuration.

Temperature is not just a setting designed to add pain to our app building efforts. It provides a way to control creativity (or maybe I should call it variability) in the output.

We may want to reduce the temperature setting for cases where we want consistency (e.g., when summarising customer chats) and increase it for when we want some level of variability (e.g., when writing a poem). It wouldn’t be any fun if two users posted the same poem written by ChatGPT!

We need to find new ways of checking the semantic correctness of the output and these types of tests are not value matching types. That is why we find ourselves increasingly dependent on other LLMs for checking unstructured input-output pairs.

In the next post we will start breaking down the llm function and understand the compositionality aspects of it. This will help us understand where that extra information is coming from that don’t allow us to make reasonable assumptions about outputs.

2 Comments