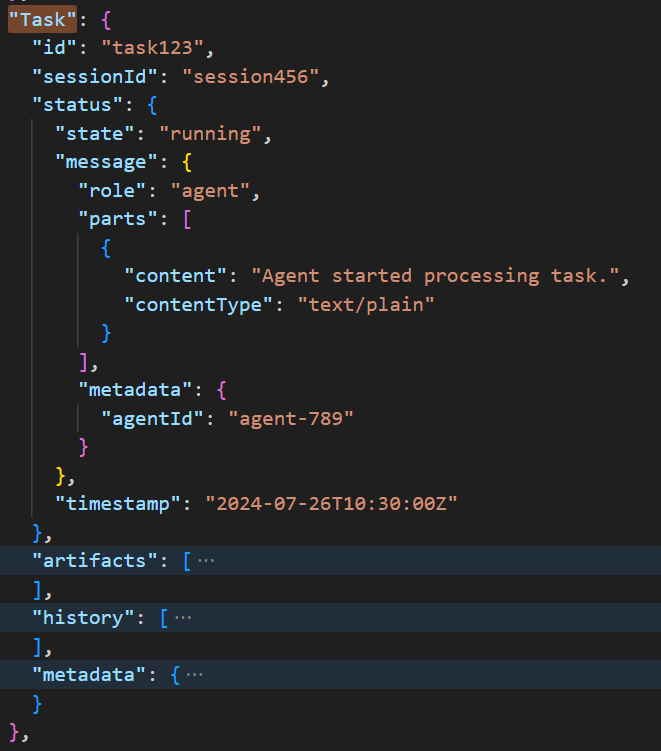

This post attempts to map Conversational Patterns to Agentic AI. This is because a project must not start with: ‘I want to use agentic to solve this problem’.

Instead it must say: ‘I need agentic to support the style of conversational experience that best solves this problem’.

Layers of Conversation

Every conversation over a given channel occurs between an interested/impacted party and the organisation (e.g., customer over webchat, colleague over the phone). Every conversation has an outcome: positive/negative customer party outcome or positive/negative organisational outcome.

Ideal outcome being positive for both but not always possible.

There are several layers in this conversation and each layer allows us to map to different tasks for automation.

- Utterance – this is basically whatever comes out of the customer or colleagues (referred to as the ‘user’) mouth – process this to extract Intents and Constraints.

- Intent and constraints – this is the intent and constraints processed to align them with organisational intents and constraints and thereafter extracting a set of actions to achieve them.

- Actions – this is each action decomposed into a set of ordered steps.

- Steps – this is each step being converted into a sequence of interactions (or requests) to various back-end systems.

- Request – this is each request being made and the response processed including errors and exceptions.

Utterance

The key task for an utterance is the decomposition into intents (what does the user want to achieve?) and constraints (what are the constraints posed by the user?). The organisational intent and constraints are expected to be understood. I am assuming here that a level of customer context (i.e., who is the customer) is available through various ‘Customer 360’ data products.

Example: ‘I want to buy a house’ -> this will require a conversation to identify intent and constraints. A follow up question to the user may be ‘Amazing, can I confirm you are looking to discuss a mortgage today?’.

Key Task: Conversation to identify and decompose intents and constraints.

AI Capability: Highly capable conversational LLM (usually a state of the art model that can deal with the uncertainty).

The result of this decomposition would be an intent (‘buying a house with a mortgage’) with constraints (amount to be borrowed, loan-to-value, term of loan etc.). Once are a ready we can move to the next step.

Intents and Constraints

Once the intent and constraints have been identified they need to be aligned with the organisational intents and constraints using any customer context that is available to us. This is critical because this is where we want to trap requests that are either not relevant or can’t be actioned (e.g., give me a 0% life-long mortgage – what a dream!). Another constraint can be if the customer is new – which means we have no data context.

If these are aligned with the organisation then we decompose these into a set of actions. These actions be at a level of abstraction and not mapped to specific service workflows. This step helps validate the decomposition of intents and constraints against the specific product(s) and associated journeys.

Example: Buying a house on a mortgage – specific actions could include:

- Collect information from the customer to qualify them.

- Do fraud, credit and other checks.

- Provide agreement in principle.

- Confirm terms and conditions.

- Process acceptance.

- Initiate the mortgage.

Key Task: Mapping intents to products and associated journeys using knowledge of the product.

AI Capability: The model being able to map various pieces of information to specific product related journeys. This will usually also require state of the art LLMs but can be supported by specific ‘guides’ or Small Language Models (SLMs). This can especially be useful if there are multiple products with similar function but very subtle acceptance criteria (e.g., products available to customers who have subscribed to some other product).

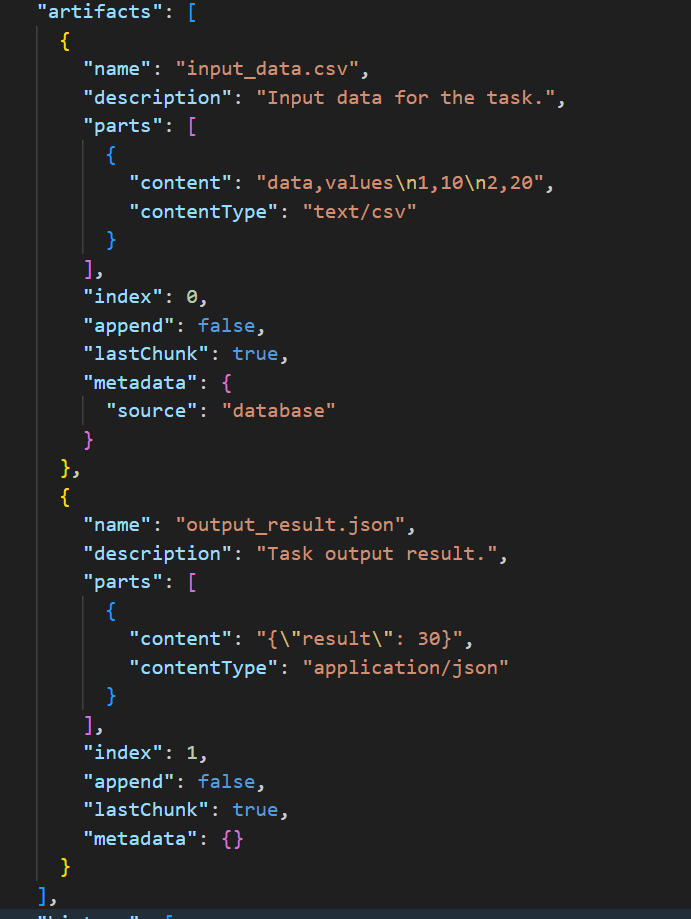

Actions

This is where the fun starts as we start to worry about the ‘how’ part. As we now have the journeys associated with the interaction the system can start to decompose these into a set of steps. There will be a level of optimisation and orchestration involved (this can be machine led or pre-defined) and the complexity of the IT estate starts to become a factor.

Example: Collect information from the customer and Checks.

Now the system can decide whether we collect and check or check as we collect. Here the customer context will be very important as we may or may not have access to all the information beforehand (e.g., new customer). So depending on the customer context we will decompose the Collect information action into few or many steps. These steps can be interleaved with the steps we get by decomposing the ‘Checks’ action.

By the end of this we will come up with a set of steps (captured in one or more workflows) that will help us achieve the intent without breaking customer or org constraints:

Assuming a new customer wants to apply for a mortgage…

- Collect basic information to register a new customer.

- [Do Fraud checks]

- Create customer’s record.

- Create customer’s application within the customer’s account.

- Collect personal information.

- Collect expense information.

- Collect employment information.

- Seek permission for credit check

- [Do credit check or stop application.]

- Collect information about the proposed purchase.

- Collect information about the loan parameters.

- Qualify customer.

Key Tasks: The key task here is to ‘understand’ the actions, the dependencies between them and then to decompose them into a set of steps and orchestrate them into the most optimal workflow. Optimal can mean many things depending on the specific journey. For example, a high financial value journey like a mortgage for a new customer might be optimised for risk reduction and security even if the process takes a longer time to complete but for an existing mortgage customer it may be optimised for speed.

AI Capability: Here we can do with SLMs as a set of experts and a LLM as the primary orchestrator. We want to ensure that each Action -> Step decomposition is accurate as well as the merging into a set of optimised workflows is also done correctly.

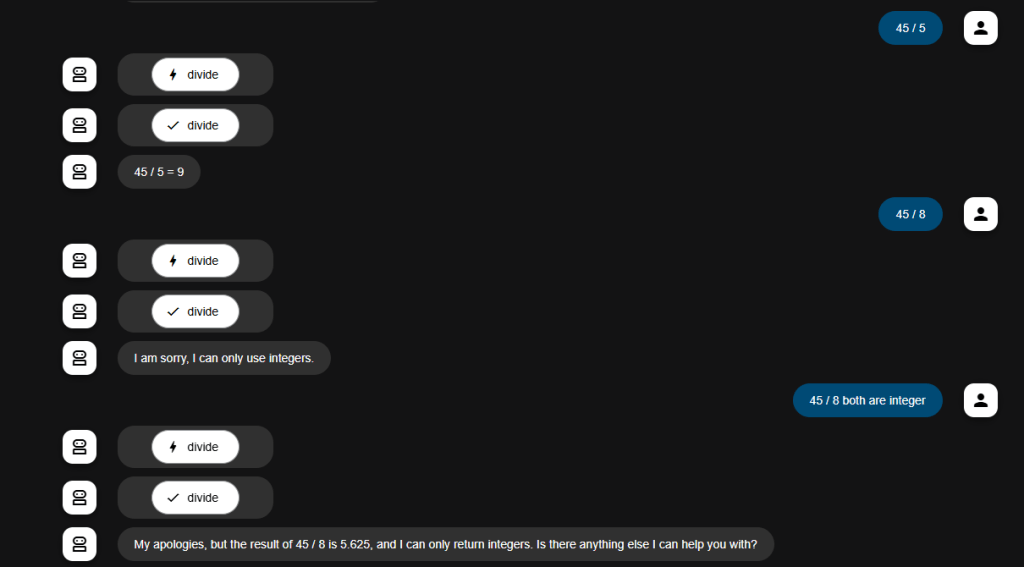

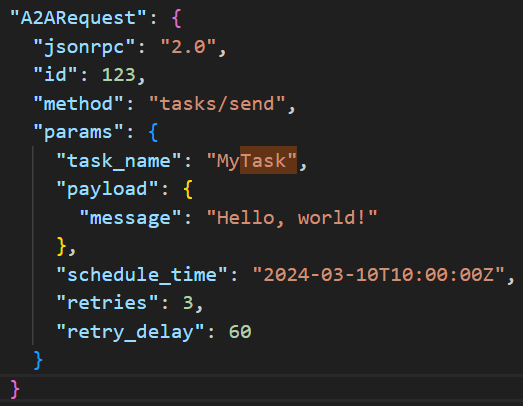

Steps and Requests

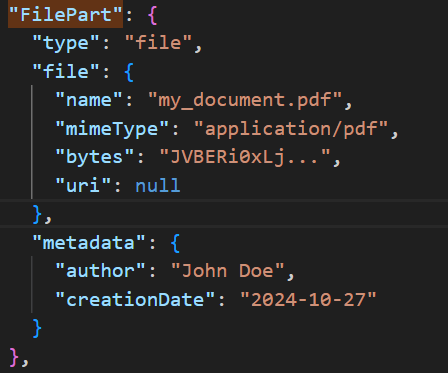

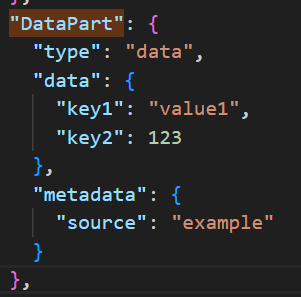

Once we get a set of steps we need to decompose these into specific requests. The two steps are quite deeply connected as here the knowledge of how Steps can be achieved is critical and this is also dependent on the complexity of the IT estate.

Example: Collect basic information to register a new customer.

Given the above step we will have a mix of conversational outputs as well as function calls at the request level. If our IT estate is fragmented then whilst we collect the information once (minimal conversational interaction with the customer) our function calls will look very complex. In many organisations customer information is stored centrally but it requires ‘shadows’ to be created in several different systems (e.g., to generate physical artefacts like credit cards, passcode letters etc.). So your decomposition to requests would look like:

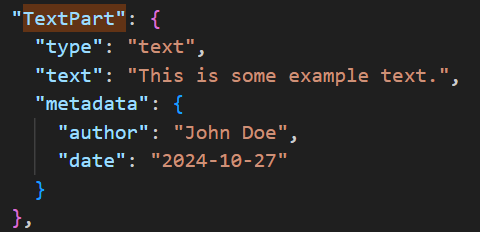

- Conversation: Collect name, date of birth, … from the customer.

- Function calling (reflection): check if customer information makes sense and flag if you detect any issues

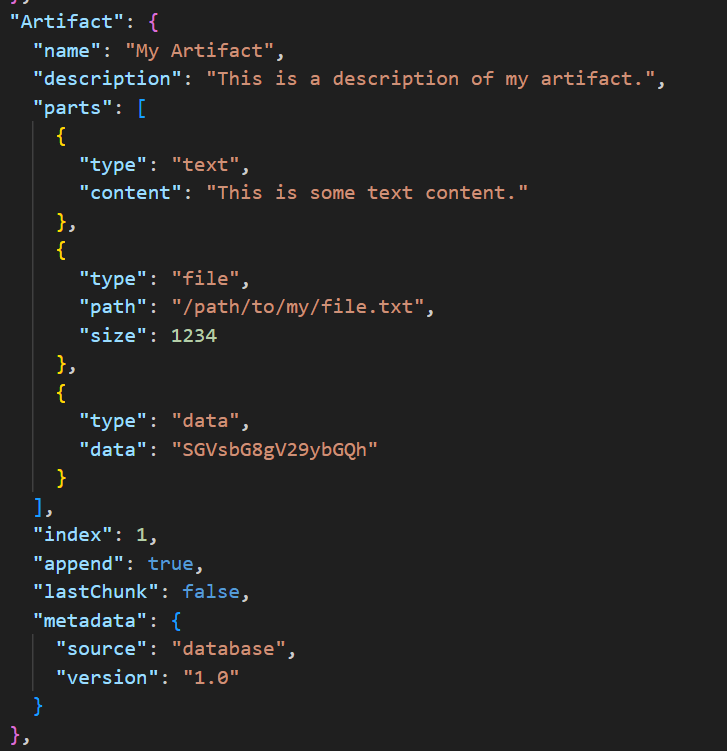

- Function calling: Format data into JSON object with the given structure and call the ‘add_new_customer’ function (or tool).

Now the third step ‘Format data into JSON… ‘ could be made up of multiple critical and optional requests implemented within the ‘add_new_customer’ tool:

- Create master record for customer and obtain customer ID. [wait for result or fail upon issues]

- Initiate online account and app authorisation for customer using customer ID. [async]

- Initiate physical letter, card, pins, etc. using customer information. [async]

- Provide customer information to survey platform for a post call ‘onboarding experience survey’ [async]

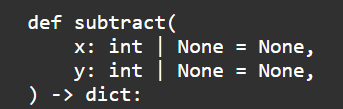

Key Tasks: The key tasks here are to understand the step decomposition into requests and the specific function calls that make up a given request.

AI Capability: Here specific step -> request decomposition and then function calling capabilities are required. SLMs can be of great help here especially if we find that step to request decomposition is complex and requires dynamic second level orchestration. But pre-defined orchestrated workflows can also work well here.

Next post on how we can use Agentic AI to support Conversations: https://fisheyeview.fisheyefocus.com/2025/06/22/agentic-ai-to-support-conversations/