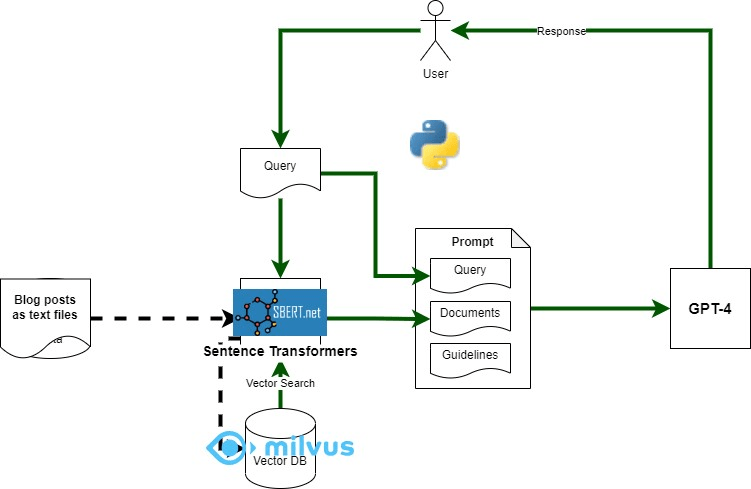

This is the fourth post in the Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) series where we look at using LangChain to implement RAG.

If you just want the code – the link is just before the Conclusion section at the end of the post.

At its core, LangChain is a python library that contains tools for common tasks that can be chained together to build apps that process natural language using an AI model.

The LangChain website is quite good and has lots of relevant examples. One of those examples helped write a LangChain version of my blog RAG experiment.

This allows the developer to focus on building these chains using the available tools (or creating a custom tool where required) instead of coding everything from scratch. Some common tasks are:

- reading documents of different formats from a directory or some other data-source

- extracting text and other items from those documents (e.g., tables)

- processing the extracted text (e.g., chunking, stemming etc.)

- creating prompts for LLMse based on templates and processed text (e.g., RAG)

I first implemented all these tasks by hand to understand the full end-to-end process. But in this post I will show you how we can achieve the same result, in far less dev time, using LangChain.

Introduction to LangChain

Langchain is made up of four main components:

- Langchain – containing the core capability of building chains, prompt templates, adapters for common providers of LLMs (e.g., HuggingFace).

- Langchain Community – this is where the tools added by the Langchain developer community live (e.g., LLM providers, Data-store providers, and Document loaders). This is the true benefit of using Langchain, you are likely to find common Data-stores, Document handling and LLM providers already integrated and ready for use.

- LangServe – to deploy the chains you have created and expose them via REST APIs.

- LangSmith – adds observability, testing and debugging to the mix, needed for production use of LangChain-based apps.

More details can be found here.

Install LangChain using pip:

Key Building Blocks for RAG mapped to LangChain

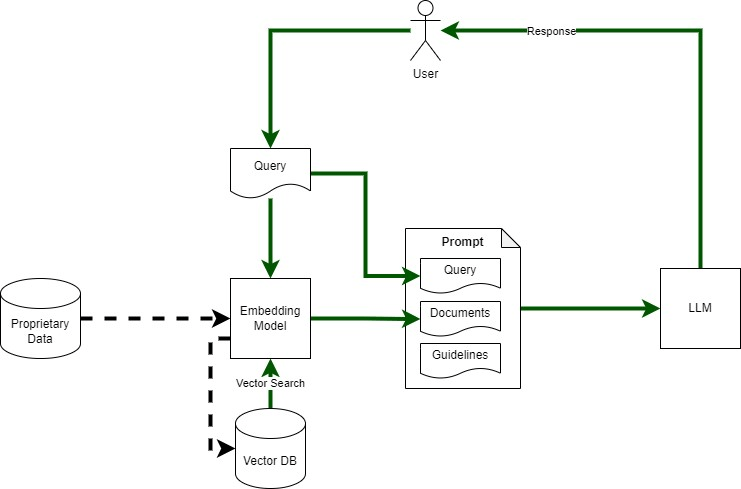

The simplest version of RAG requires the following key building blocks:

- Text Extraction Block – dependent on type of data source and format

- Text Processing Block – dependent on use-case and vectorisation method used.

- Vector DB (and Embedding) Block – to store/retrieve data for RAG

- Prompt Template – to integrated retrieved data with the user query and instructions for the LLM

- LLM – to process the question and provide a response

Text Extraction can be a tedious task. In my example I had converted my blog posts to a set of plain text files which meant that reading them was simple. But what if you have a bunch of MS Word docs or PDFs or HTML files or even Python source code? The text extractor has to then process structure and encoding. This can be quite a challenging task especially in a real enterprise where different versions of the same format can exist in the same data source.

LangChain Community provides different packages for dealing with various document formats. These are contained in the following package:

langchain_community.document_loaders

With the two lines of code below you can load all the blog post text files from a directory (with recursion) in a multi-threaded manner into a set of documents. It also populates the document with its source as metadata (quite helpful if you want to add references in the response).

dir_loader = DirectoryLoader("\\posts", glob="**/*.txt", use_multithreading=True)<br>blog_docs = dir_loader.load()

Check here for further details and available document loaders.

Text Processing is well suited for this ‘tool-chain’ approach since it usually involves chaining a number of specific processing tasks (e.g., extract text from the document and remove stop words from it) based on the use-case. The most common processing task for RAG is chunking. This could mean chunking a text document by length, paragraphs or lines. Or it could involve chunking JSON text by documents. Or code by functions and modules. These are contained in the following package:

With the two lines below we create a token-based splitter (using TikToken) that splits by fixed number of tokens (100) with an overlap of 10 tokens and then we pass it the blog documents from the loader to generate chunked docs.

text_splitter = TokenTextSplitter.from_tiktoken_encoder(chunk_size=100, chunk_overlap=10)

docs = text_splitter.split_documents(blog_docs)

Check here for further details and available text processors.

Vector DB integration took the longest because I had to learn to setup Milvus and how to perform read/writes using the pymilvus library. Not surprisingly, different vector db integrations are another set of capabilities implemented within LangChain. In this example instead of using Milvus, I used Chroma as it would do what I needed and a one-line integration.

For writing into the vector db we will also need an embedding model. This is also something that LangChain provides.

The following package provides access to embedding models:

The code below initialises the selected embedding model and readies it for use in converting the blog post chunks into vectors (using the GPU).

EMBEDDING_MODEL = "sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L12-v2"

emb_kw_args = {"device":"cuda"}

embeddings = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(model_name=EMBEDDING_MODEL, model_kwargs=emb_kw_args)

The vector store integrations can be found in the following package:

langchain_community.vectorstores

Further information on vector store integrations can be found here.

The two lines below first setup the Chroma database and write the extracted and processed documents with the selected embedding model. The first line takes in the chunked documents, the embedding model we initialised above, and the directory we want to persist the database in (otherwise we can choose to run the whole pipeline every time and recreate the database every time). This is the ‘write’ path in one line.

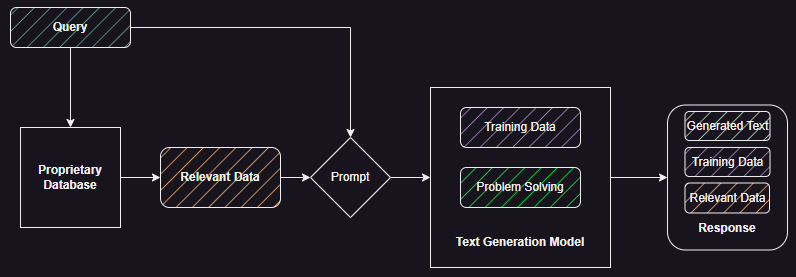

db = Chroma.from_documents(docs, embeddings, persist_directory="./data") retriever = db.as_retriever()

The second line is the ‘read’ path again in one line. This creates a retriever object that we can add to the chain and use it to retrieve, at run time, documents related to the query.

Prompt Template allows us to parameterise the prompt while preserving its structure. This defines the interface for the chain that we are creating. To invoke the chain we will have to pass the parameters as defined using the prompt template.

The RAG template below has two variables: ‘context’ and ‘question’. The ‘context’ variable is where LangChain will inject the text retrieved from the vector db. The ‘question’ variable is where we inject the user’s query.

rag_template = """Answer only using the context.

Context: {context}

Question: {question}

Answer: """

The non-RAG template shown below has only one variable ‘question’ which contains the user’s query (given that this is non-RAG).

non_rag_template = """Answer the question: {question}

Answer: """

The code below sets up the objects for the two prompts along with the input variables.

rag_prompt = PromptTemplate(template=rag_template, input_variables=['context','question'])

non_rag_prompt = PromptTemplate(template=non_rag_template, input_variables=['question'])

The different types of Prompt Templates can be found here.

LLM Block is perhaps the central reason for the existence of LangChain. This block allows us to encapsulate any given LLM into a ‘tool’ that can be made part of a LangChain chain. The power of the community means that we have implementations already in place for common providers like OpenAI, HuggingFace, GPT4ALL etc. Lots of code that we can avoid writing, particularly if our focus is app development and not learning about LLMs. We can also create custom handlers for LLMs.

The package below contains implementations for common LLM providers:

Further information on LLM providers and creating custom providers can be found here.

For this example I am running models on my own laptop (instead of relying on GPT4 – cost constraints!). This means we need to use GPT4ALL with LangChain (from the above package). GPT4ALL allows us to download various models and run them on our machine without writing code. They also allow us to identify smaller but capable models with inputs from the wider community on strengths and weaknesses. Once you download the model files you just pass the location to the LangChain GPT4ALL tool and it takes care of the rest. One drawback – I have not been able to figure out how to use the GPU to run the models when using GPT4ALL.

For this example I am using ORCA2-13b and FALCON-7b. All it takes is one line (see below) to prepare the model (in this case ORCA2) to be used in a chain.

gpt4all = GPT4All(model=ORCA_MODEL_PATH)

The Chain in All Its Glory

So far we have setup all the tools we will need to implement RAG and Non-RAG chains for our comparison. Now we bring all of them on to the chain which we can invoke using the defined parameters. The cool thing is that we can use the same initialised model on multiple chains. This means we also save time coding the integration of these tools.

Let us look at the simpler Non-RAG chain:

non_rag_chain = LLMChain(prompt=non_rag_prompt, llm=gpt4all)

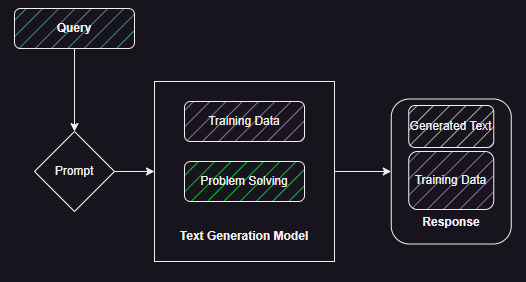

This uses LLMChain (available as part of the main langchain package). The chain above is the simplest possible – which is doing nothing but passing a query to the LLM and getting a response.

Let us see the full power of LangChain with the RAG chain:

rag_chain = (

{"context": retriever | format_docs , "question":RunnablePassthrough()} | rag_prompt | gpt4all

)

The chain starts off by populating the ‘context’ variable using the vector db retriever and ‘format_docs‘ function we created. The function simply concatenates the various text chunks retrieved from the vector database. The variable ‘question’ is sent to the retriever as well as passed through to the rag_prompt (as defined by the template). Following this the output from the prompt template is passed to the model encapsulated by gpt4all object.

The retriever, rag_prompt, and gpt4all objects are all tools that we created using LangChain. ‘format_docs‘ is a simple python function that I created. We can use the ‘run’ method on the LLMChain and the ‘invoke’ method on the RAG chain to execute the pipeline.

The full code is available here.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post will help you take the first steps in building Gen AI apps using LangChain. While it was quite easy to learn and build applications using LangChain, it does have some drawbacks when compared to building your own pipeline.

From a learning perspective LangChain hides lot of the complexities or exposes them through argument lists (e.g., running embedding model on GPU). This might be good or bad depending on how you like to learn and what your learning target is (LLM vs just building Gen AI app).

Frameworks also fix the way of doing something. If you want to explore different options of doing something then write your own code. Best approach may be to use LangChain defined tools for the ‘boilerplate’ parts of the code (e.g., loading documents) and your own code (as shown with the ‘format_doc’ function) where you want to dive deeper. The pipeline does not need to have a Gen AI model to run. For example, you could just create a document extraction chain and integrate manually with the LLM.

There is also the issue with understanding how to productionise the app. LangSmith offers lot of the capabilities but given that this framework is relatively new it will take time to mature.

Finally Frameworks also follow standard architecture options. Which means if our components are not part of a standard architecture (e.g., we are running models independently of any ‘runner’ like GPT4ALL), as can be the case in an enterprise use-case, then we have to build out LangChain custom model wrapper that allows us to integrate it with the chain.

Finally, frameworks can come and go. We still remember the React vs Angular choice. It is usually difficult to get developers who know more than one complex framework. The other option in this space, for example, is LlamaIndex. If you see the code examples in the link you will find similar patterns of configuring the pipeline.