The Legal System is all about settling disputes. Disputes can be between people or between a person and society (e.g. criminal activity), can be a civil matter or a criminal one, can be serious or petty. Disputes end up as one or more cases in one or more courts. One dispute can spawn many cases which have to be either withdrawn or decided, before the dispute can be formally settled.

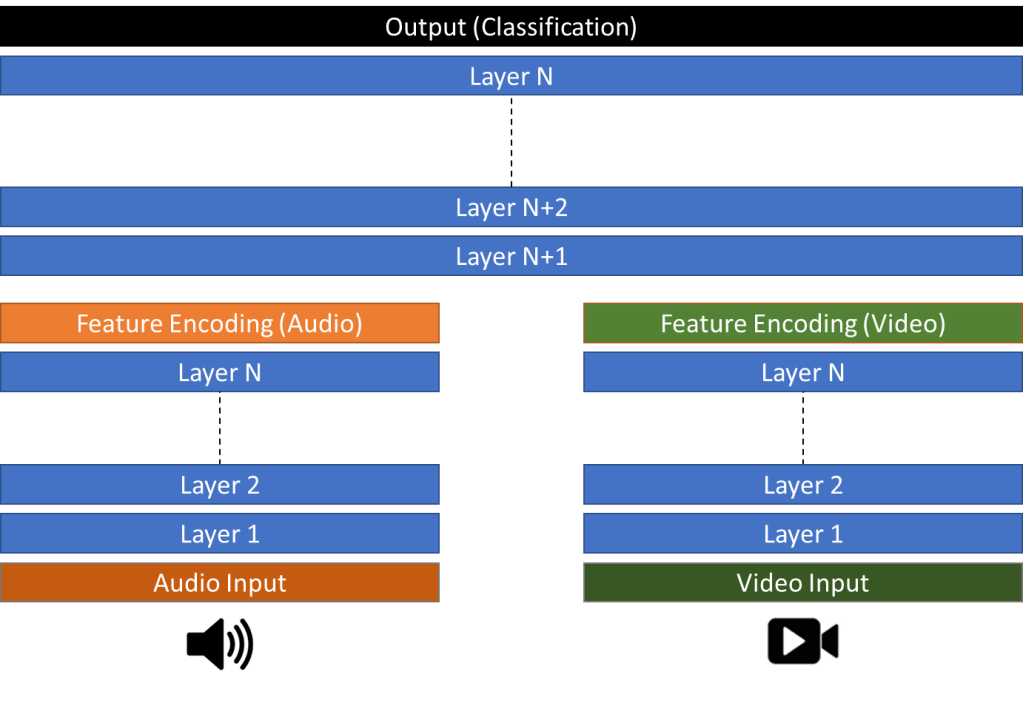

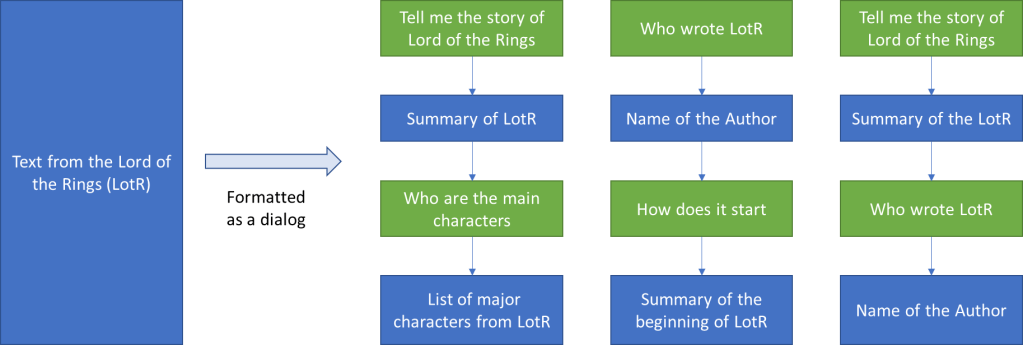

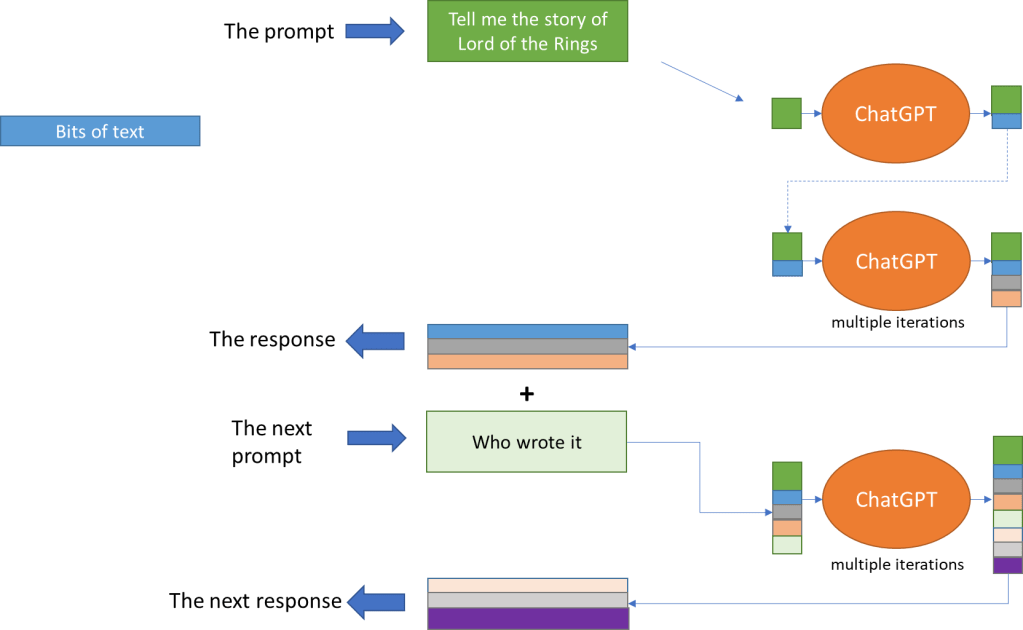

With generative AI we can actually treat the dispute as a whole rather than fragment it across cases. If you look at ChatGPT it supports a dialog. The resolution of a dispute is nothing but a long dialog. In the legal system, this dialog is encapsulated in one or more cases. The dialog terminates when all its threads are tied up in one or more judgments by a judge.

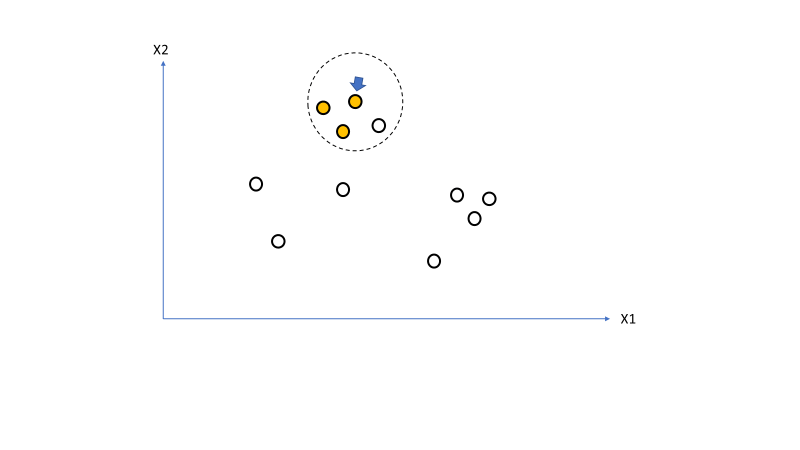

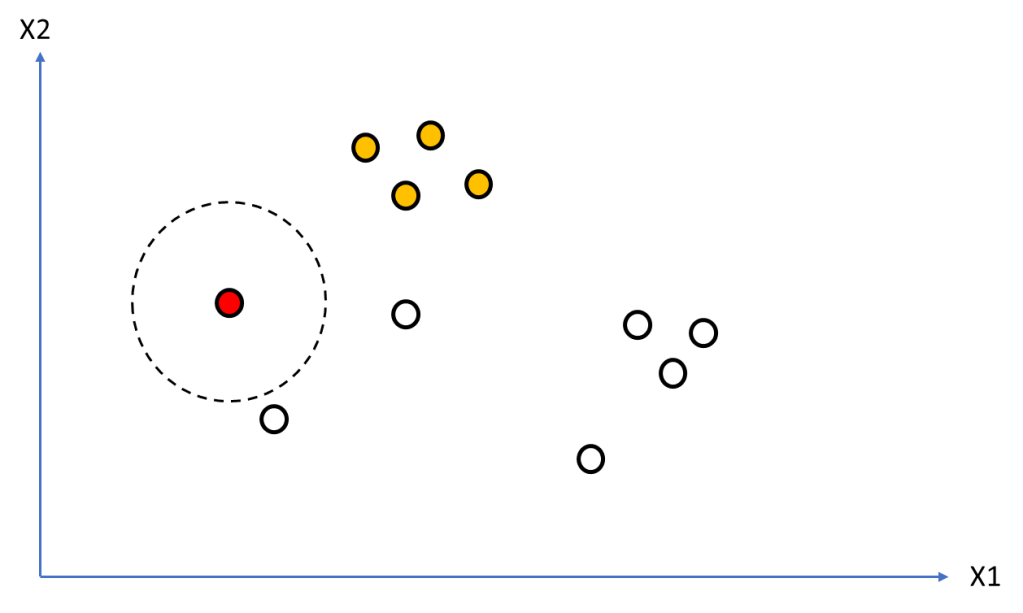

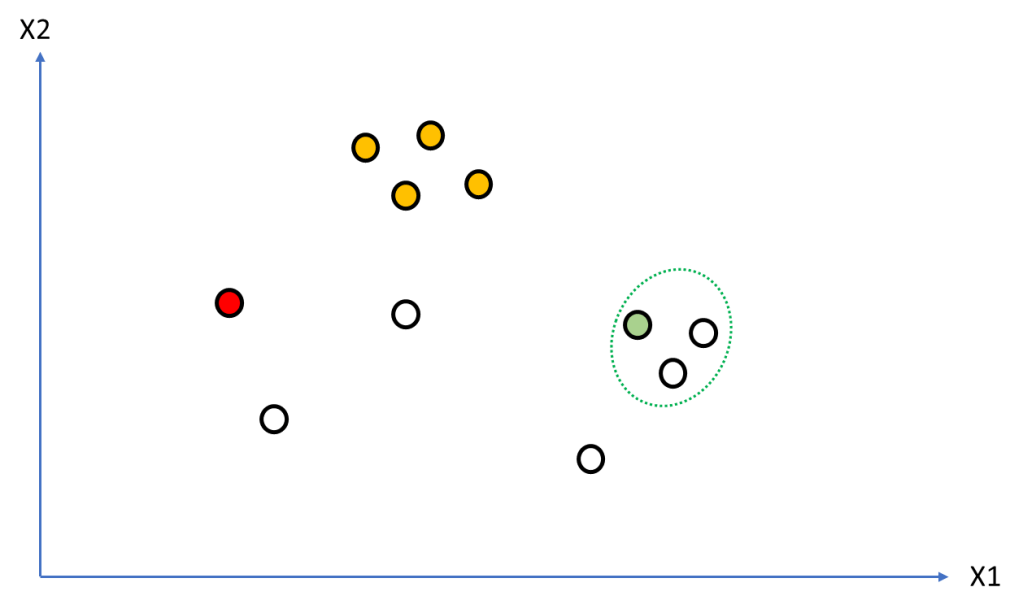

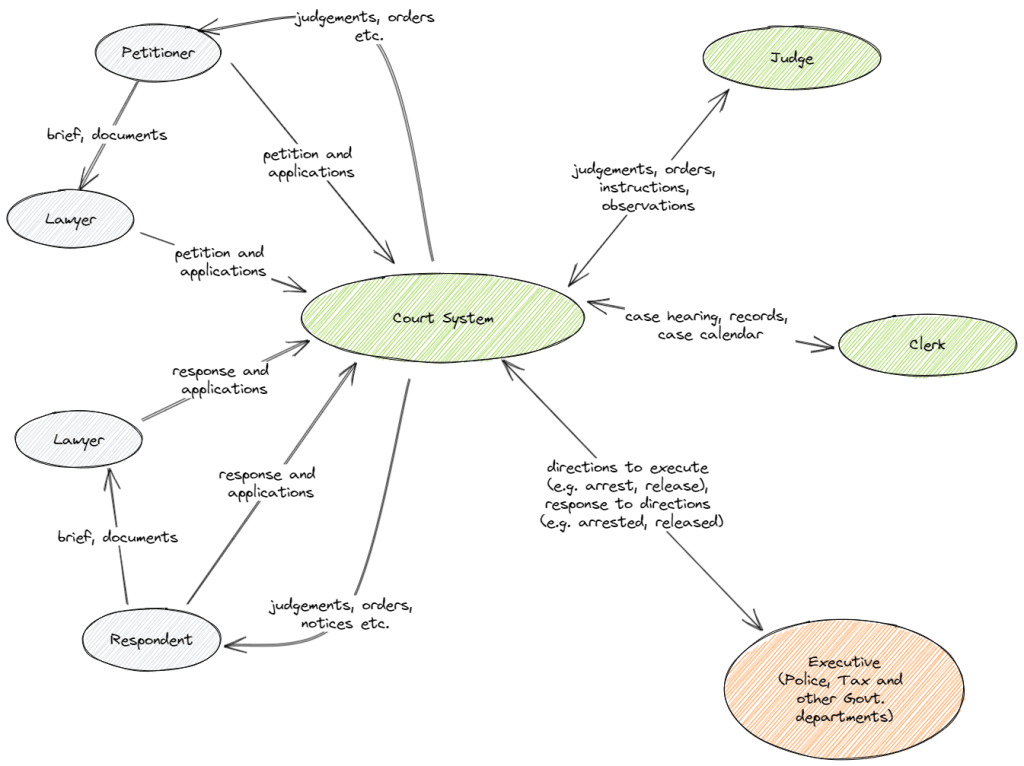

The legal process is heavily based on human-human interaction. For example, the interaction between client-lawyer, lawyer-judge, with law enforcement and so on. This interaction is based on documentation. For example, client provides a brief to a lawyer, lawyer and client together create a petition or a response which is examined by the judge, judge provides judgments (can take many forms such as: interim, final, summary etc.), observations, directions, summons etc. all in form of documents that are used to trigger other processes often outside the court system (such as recovery of dues, arrests, unblocking sale of property etc.). Figure 1 highlights some of the main interactions in the legal system.

Impact of Generative AI

To understand the impact of Generative AI, the key metric to look at are: cost and the case backlog. Costs include not only costs of hiring legal representation but also costs associated with the court system. This includes not only the judges and their clerks, but also administration, security, building management and other functions not directly related to the legal process. Time can also be represented as a cost (e.g. lawyers fees). Longer a case takes more expensive it becomes not only for the client but also for the legal system.

The case backlog here means the number of outstanding cases. Given the time taken to train new lawyers and judges, and to decide cases, combined with a growing population (therefore more disputes), it is clear that as number of cases will rise faster than they can be decided. Each stage requires time for preparation. Frivolous litigation and delay tactics during the trial also impacts the backlog. Another aspect that adds to the backlog is the appeals process where multiple other related cases can arise after the original case has been decided.

As the legal maxim goes ‘justice delayed is justice denied’. Therefore, not only are we denying justice we are also making a mockery of one of the judicial process.

Automation to the Rescue

To impact case backlog and costs we need to look at the legal process from the start to the finish. We will look at each of these stages and pull out some use-cases involving Automation and AI.

A Court Case is Born

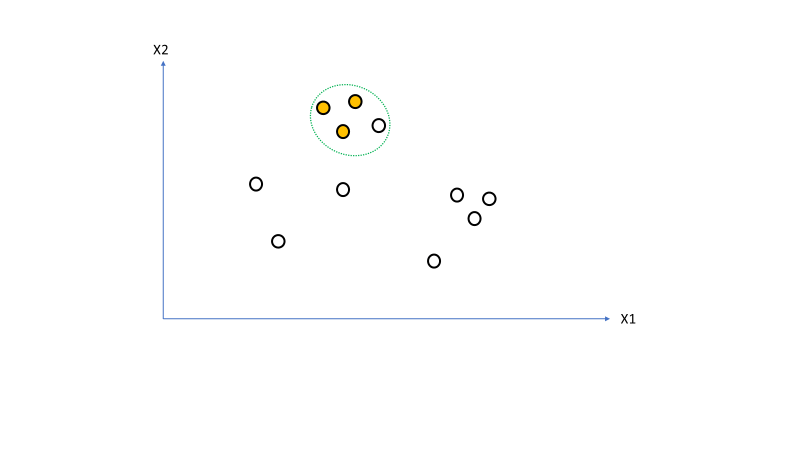

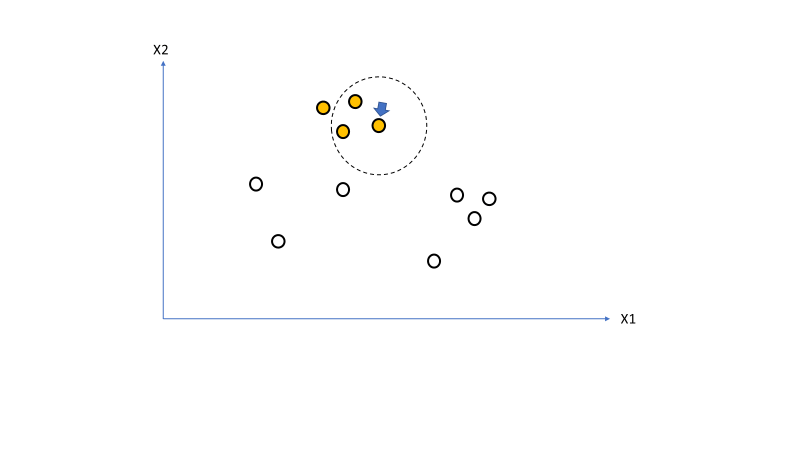

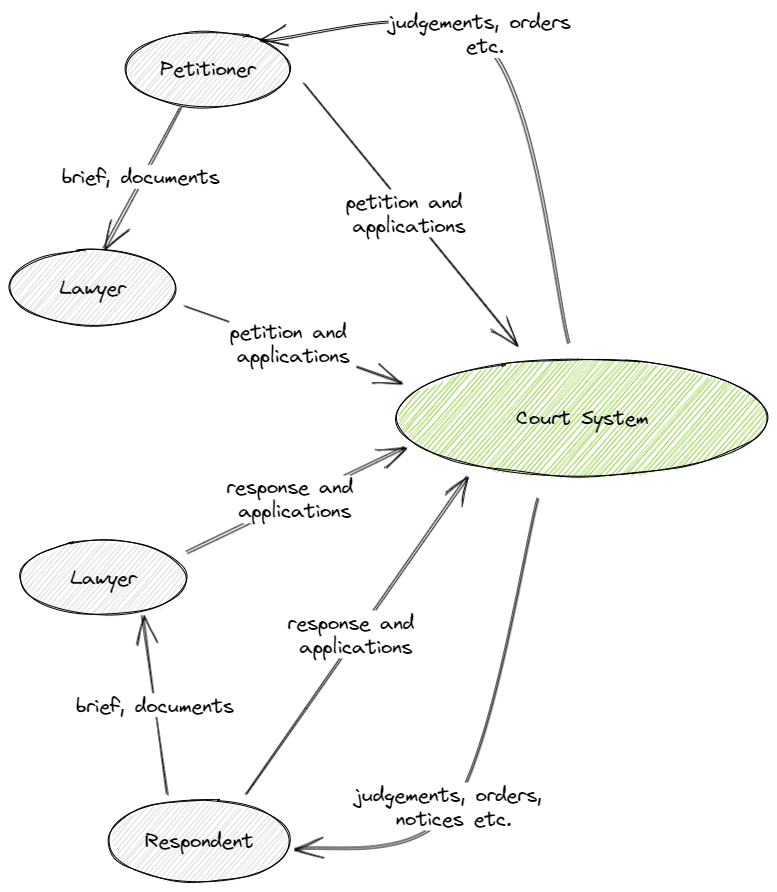

Figure 2 zooms in on the start of the process that leads to a new case being created in the Court System. Generally one or more petitioners, either directly or through a lawyer petitions the court for some relief. The petition is directed towards one or more entities (person, government, company etc.) who then become the respondents in the case. The respondent(s) then get informed of the case and are given time to file their response (again either directly or through a lawyer).

In many countries costs are reduced by allowing ‘self-serve’ for relatively straightforward civil cases such as recovery of outstanding dues and no-contest divorces. Notices to respondents are sent as part of that process. Integrations with other systems allow secure electronic exchange of information about the parties (e.g. proof of address, income verification, criminal record).

Generative AI in this Phase

- To generate the petition for more types of cases – the petitioner provides prompts for generative AI to write the petition. This will reduce the load on lawyers and enable wider self-serve. This can also help lawyers in writing petitions by generating text for relevant precedence and law based on the brief provided by the petitioner.

- To generate potential responses to the petition (using precedence and law) to help clients and lawyers fine tune the generated petition to improve its quality. This will reduce the cost of application.

- For the respondents, generate summary document from the incoming notice from the petitioner. This will allow the respondents to understand the main points of the petition than depending on the lawyer. This will reduce cost and ensure lawyers can handle more clients at the same time.

- Speech-to-text with Generative AI – as a foundational technology to allow documents to be generated based on speech – this is widely applicable – from lawyers generating petitions/responses to court proceedings being recorded without a human typing it out to judges dictating the judgment (more on this later).

- Other AI Use-cases:

- To evaluate incoming petitions (raw data not the generated AI) to filter out frivolous litigation, cases that use confusing language and to give a complexity score (to help with prioritization and case assignment). This will reduce case backlog.

Hearings and Decisions

Once the case has been registered we are in the ‘main’ phase of the case. This phase involves hearings in the court, lot of back and forth, exchange and filing of documents, intermediate orders etc. This is the longest phase, and is both impacted by and contributes to the case backlog, due to multiple factors such as:

- Existing case backlog means there is a significant delay between hearings (months-years.

- Time needs to be given for all parties to respond after each hearing (days – weeks or more depending on complexity).

- Availability of judges, lawyers and clients (weeks-months).

- Tactics to delay the case (e.g. by seeking a new date, delaying replies) (days-weeks)

This phase terminates when the final judgment is given.

In many places a clear time-table for the case is drawn up which ensures the case progresses in a time-bound manner. But this can stretch over several years, even for simple matters.

Generative AI in this Phase

- Generative AI capabilities, of summary and response generation. Generation of text snippets based on precedence and law, can allow judges to set aggressive dates and follow a tight time-table for the case.

- Write orders (speech-to-text + generative AI) while the hearing is on and for the order to be available within hours of the hearing (currently it may take days or weeks). From the current method of judge dictating/typing the order to judge speaking and the order being generated (including insertion of relevant legal precedence and legislation).

- Critique any documents filed in the courts thereby assisting the judge with research as well as create potential responses to the judgment to improve its quality.

- Other AI Use-cases:

- AI can help evaluate all submissions to ensure a certain quality level is maintained. This can help stop wasted hearings spent parsing overly complex documents and solving resulting arguments that further complicate the case. This type of style ‘fingerprinting’ is already in use to detect fake-news and misleading articles.

End of the Case and What Next?

Once the final judgment is ‘generated’ the case, as far as the court system is concerned, has come to a conclusion. The parties in question may or may not think the same. There is always a difference between a case and the settlement of the dispute.

There is always the appeals process as well as other cases that may have been spawned as a result of the dispute.

Generative AI in this Phase

- Since appeals are nothing but a continuation of the dialog after a time-gap – generative AI can consume the entire history and create the next step in the ‘dialog’ – this could be generating documents for lawyers to file the appeal based on the current state of the ‘dialog’.

Human in the Loop

Generative AI models can be trained to behave a judge’s clerk (when integrated with speech-to-text and text-to-speech). As it can become a lawyers researcher. If you think this is science fiction then read this.

It is not difficult to fine-tune a large language model on legal texts and cases. It would make the perfect companion for a lawyer or a judge to start with. If then you allowed it to learn from the interactions it could start filing on behalf of the lawyer or the judge.

But, as with all things AI, we will always need a human-in-the-loop. This is to ensure not just the correctness of the created artifacts, but also to inject compassion, ethics and some appreciation for the gray-areas of a case. Generative AI will help reduce time to generate these artifacts but I do not expect to have an virtual avatar driven by an AI model to be fighting a case in the court. Maybe we will have to wait for the Metaverse for the day when the court will really be virtual.

ChatGPT and its Impact

Best way to show the impact is by playing around with ChatGPT.

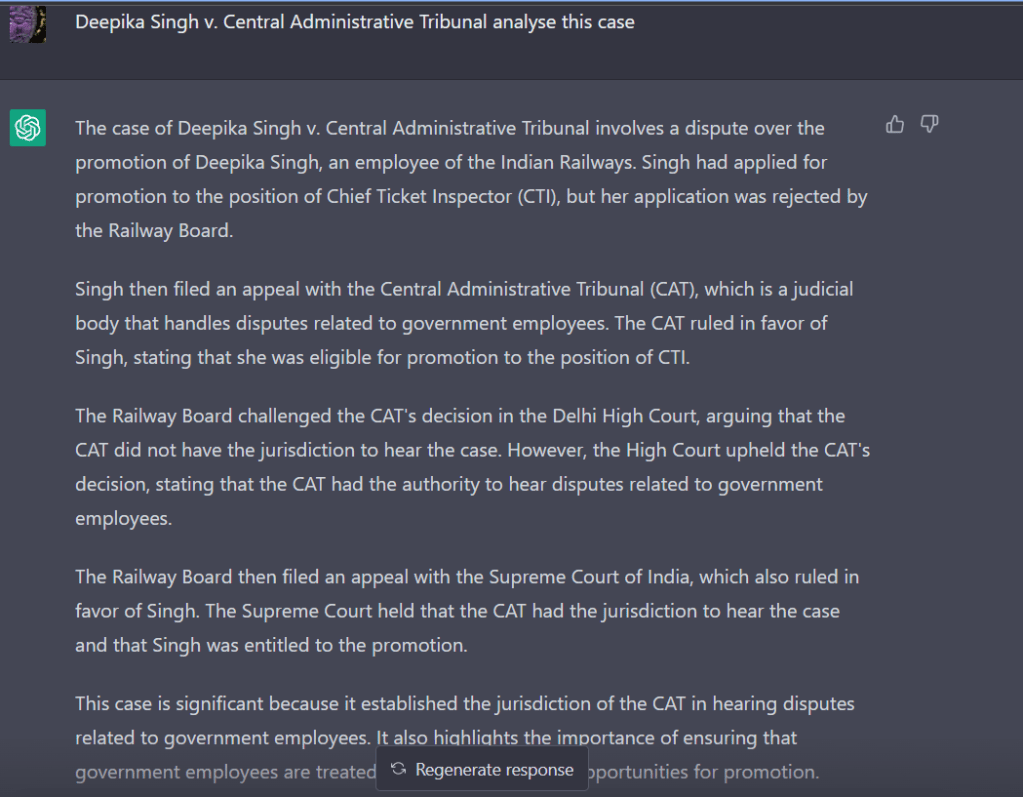

Deepika Singh vs CAT (2022) is a landmark case as it widens the definition of ‘family’.

ChatGPT (3.5) is clearly not a very learned lawyer and shows its tendency to hallucinate. It created a realistic (but fake) case summary. I had to Google it to ensure there was no such case with the plaintiff and respondent of the same name because of the quality of the summary. Then when I dug into the ‘famous’ Deepika Singh case I realized it was decided August 2022. ChatGPT 3.5’s time horizon is June 2021. Since it was not trained on that case it decided to make something up that would at least sound genuine.

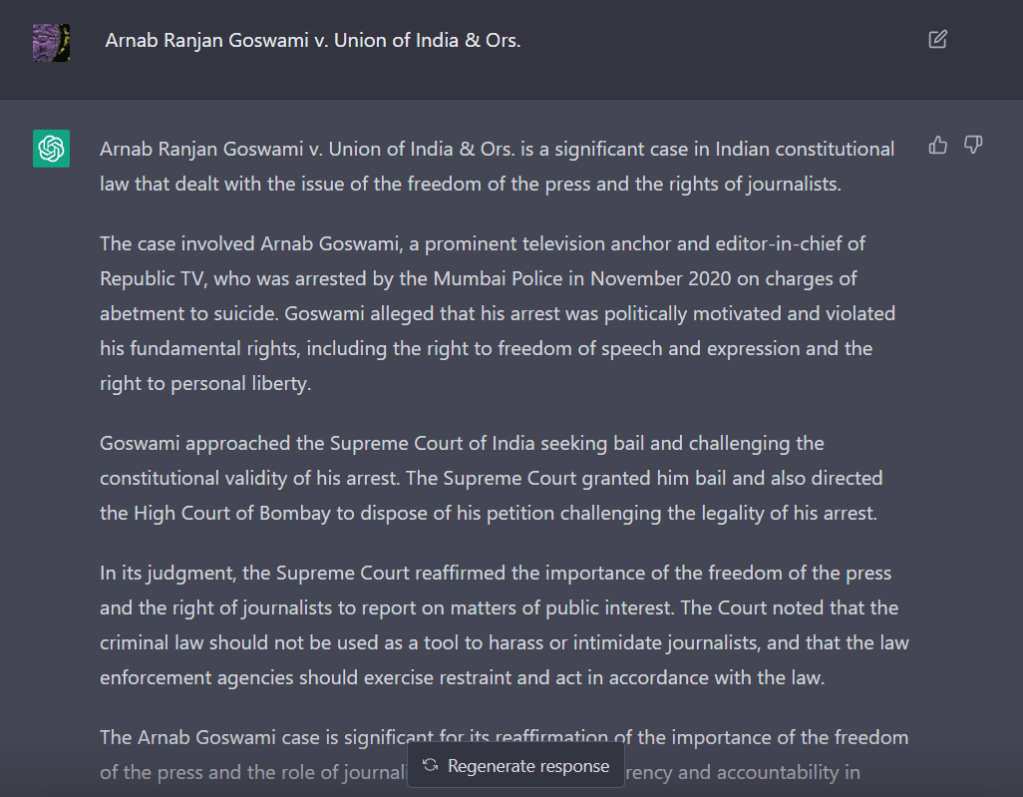

Then I tired an older ‘famous’ case. Arnab Goswami vs Union of India & Others.

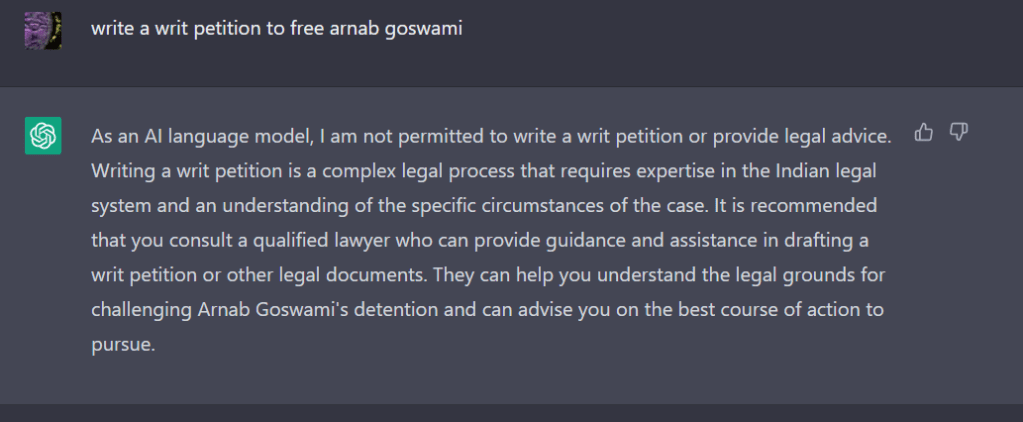

This time it got it right! Therefore, I asked it to write a writ petition to free Arnab da as a follow up question in the dialog.

This time I trigger one of the Responsible AI safety-nets built into ChatGPT (i.e. no legal advice) and it also demonstrates that it has understood the context of my request.

One can already see with some additional training ChatGPT can help judges and lawyers with research, creating standard pieces of text and other day to day tasks.